It’s that time of year when lots of people take their families and loved ones to the ballet and celebrate that classic Tchaikovsky work, The Nutcracker. Which got me thinking about toys, and how toys in fiction are often made into people, or at least people-like beings with thoughts and feelings of their own. And how heartbreaking that can often be.

Theses are the ones that stayed with us and played with us and made certain that, although we packed them up tight in cardboard boxes, we would never truly leave them behind.

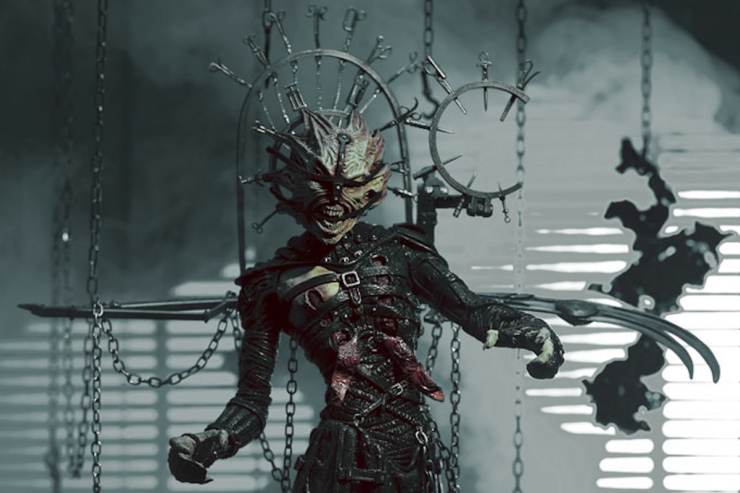

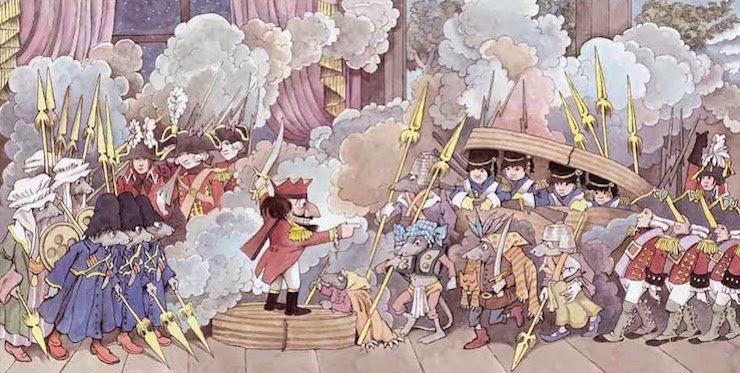

The Nutcracker

Some would argue that a nutcracker is less a toy than it is a functional tool shaped like a toy. They would be wrong. For some reason, nutcrackers retain a singular hue about them, and perhaps that is entirely due to the popularity of The Nutcracker Suite, itself an adaptation of an adaptation; the ballet was based on a story by Alexandre Dumas titled The Tale of the Nutcracker, which in turn was based on E.T.A. Hoffmann’s The Nutcracker and the Mouse King.

What is interesting about the Nutcracker’s journey is that it begins with his injury. Often stories about toys feature their wear and tear over leagues of time, but Clara’s brother Fritz instantly damages the little wooden guy, just to make his sister cry. Instead of losing something she loves, Clara gets him back life-sized and alive as a prince. And then they get crowned in a candy land. The ballet traditionally leaves the audience to decide whether or not her journey is real or the product of Christmas dreaming, but the Nutcracker represents adventure for Clara, the chance of escape and romance. And he gives her the chance to be a hero in her own right when she throws her shoe at the Rat King’s head. In the simplest of terms, this is exactly what a good toy does for a child. It’s no wonder Clara wants to fall back to sleep and find him again.

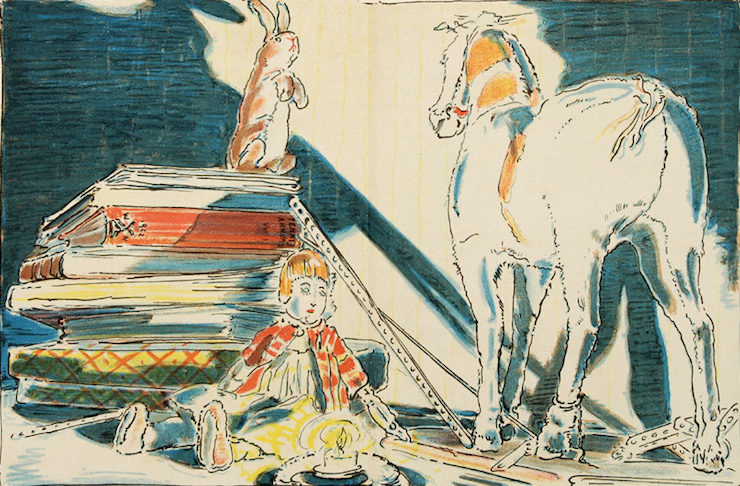

The Velveteen Rabbit

In some ways this tale feels less appropriate for children than it is for adults. The ways in which love are addressed by this book seem more akin to adult love—when the boy discards the Velveteen Rabbit (both times that he does) it is to move on to “better,” higher quality toys. Like the ex who “thought they could do better.” The themes of this tale are selflessness, love, and abandonment all in one, which is a terrifying thing to swallow as a child. There is no person I have ever met who claims that this book was merrily enlightening for them when they were young. Everyone is scarred by it.

But the tale of the Velveteen Rabbit will never leave you. It is difficult to forget how the Skin Horse sets him on the path to become Real, how he explains that the love he needs to in order to become Real is not a passing thing. It is about time and wear. About giving all of the good parts of yourself to someone else without spite or bitterness. It is something that is better understood once you have left the story far behind you. Becoming real is something that we all do in our own time. And it does hurt.

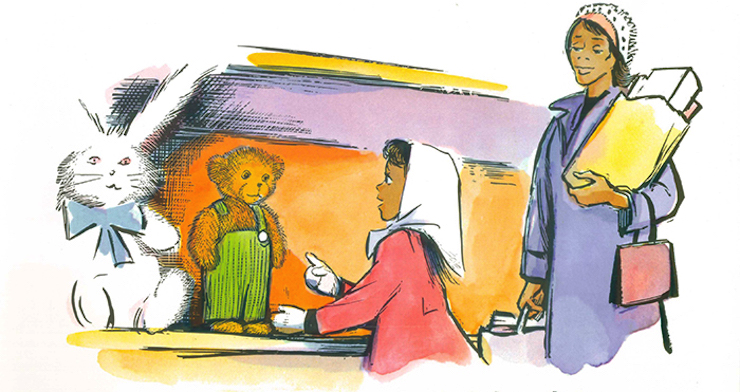

Corduroy

The journey of this department store bear can be taken many different ways. Perhaps it is a call to appreciate imperfections in others. Or seeing the worth beyond simple appearances. Or how friendship makes us whole. Whatever the reason, having his missing button pointed out by an unimpressed mother set Corduroy on the journey through the wide and cluttered halls of his store, looking for a button to make him a desirable purchase. Corduroy’s naiveté is part of what makes him so charming—it does not occur to him that his buttons should likely match, or that he doesn’t know how to sew, simply that it is something he should probably have if he ever expects to go to a nice home.

Happily, the little girl who spotted him in the first place is undaunted, and she returns the next day to buy him with her own money, then repairs his overalls herself. Corduroy’s imperfections are what draw her to him, which is often the case from a child’s perspective—his flaw makes him unique, and that uniqueness is what identifies him as the right friend for her.

I have to admit, after reading this book as a child, I was always looking for the stuffed animal with the weird ear or uncentered nose.

Pinocchio

Very similar arc to The Velveteen Rabbit at the most basic level, but ultimately a different morality at play and a different journey to achieve those goals. What makes Pinocchio fascinating is that the wooden puppet does not belong to a child—he belongs to an old man who has no child of his own. The original tale was written Carlo Collodi, and in that serial Pinocchio dies for all of his faults. But an editor’s request got Collodi to add more chapters to the story, adding more of the Fairy with Turquoise Hair (who later became the Blue Fairy in most adaptations) so that she eventually turns him into a real boy at the end.

Pinocchio has a lot in common with epic heroes—his descent into a dishonest existence has all the hallmarks of a descent into hell, and he undergoes more than one literal transformation according to his actions, into a donkey and then a real boy at last. Interestingly, both Pinocchio and the rabbit are made real by fairies who praise them for their good deeds. Apparently this is the only way to go.

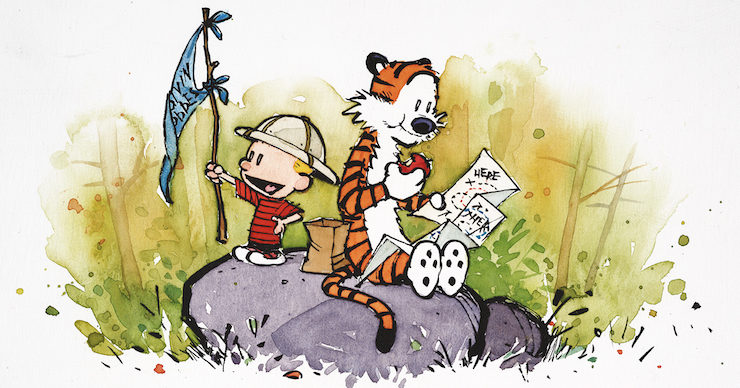

Hobbes

We love him for his need to tackle and the ongoing affair he has with tuna. But perhaps the most precious thing about Hobbes was that he was never intended to simply be Calvin’s imaginary friend made out of a stuffed tiger. Author Bill Watterson deliberately never gave readers an answer one way or the other in regards to whose reality held sway—Calvin’s or his parents’. And because of that, we were always free to believe that Hobbes was so much more than a toy.

Which was important because Calvin so desperately needed him as a foil. Calvin and Hobbes were a reminder that your toys were not just things made of stuffing and fuzz and glued-on eyes. They were true companions, the sort who could understand you when the rest of the world was completely mad. They were the ones you were free to be yourself around when kids at school were laughing or bullying. And the reality you created together was part of what defined you as you grew and changed.

Sheriff Woody

The Toy Story gang are relatively new to this crew, but they earn a spot on the list because of how sharply they illustrate a child’s relationship to toys and play and what happens as they grow apart through natural progression. The sadness of watching Woody be replaced by Buzz in the first film (and the acknowledgment of doing the same to your favorite toys as a child), the traumatizing affect that being left behind by Emily has on Jesse in the second, and finally Andy’s goodbye to his friends as he gives them a new life with a little girl who can now offer them better.

The characters of the Toy Story universe tapped something significant for a specific generation because their adventures came so many years apart. The kids who watched the first film were all grown up by the last, and in the same position as Andy—ready to leave off their childhoods, but not to let them go. It was a painfully grown up ending for a children’s film; as Andy says goodbye to his friends, we had to do the same, and in doing so we were forced to acknowledge our passage out of this place.

But even that is nothing compared to the final resonating message we are left with: Do not give up on these things you loved when you were young and bright and full of wonder. Pass them on.

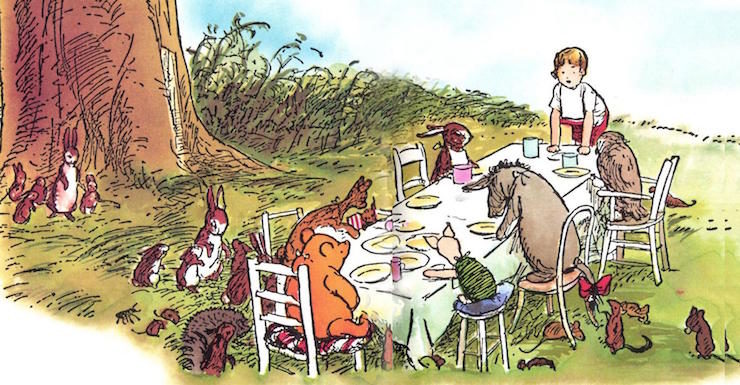

Winnie-the-Pooh

Perhaps the greatest example of toys come to life, Pooh and his friends began as Christopher Robin Milne’s actual stuffed animals before his father, A.A. Milne, turned them into characters for his children’s stories (along with Christopher Robin himself… though that’s a story for another time). Their adventures are known to multitudes of children thanks to the prevalence of Disney marketing, but nothing can quite match the charm of Milne’s original tales, full of poetry and made-up creatures and wonderful plays on words.

At the heart of all adventures in the Hundred Acre Wood (itself a reflection of the Five Hundred Acre Wood in Ashdown Forest, Sussex) was Winnie-the-Pooh, a bear named after both a swan called Pooh and a bear from the London Zoo named Winnie, who came to England via a Canadian officer during World War One. Pooh still appeals to children and adults alike because his pleasures are simple, his needs are few, and he writes the most delightful stories. He also has a blunt wisdom about him that makes him the perfect children’s hero. He may not be quick to action, but he is an adoring and sure friend who will last a lifetime. Or as Milne put it:

“If you live to be a hundred, I want to live to be a hundred minus one day so I never have to live without you.”

–Winnie-the-Pooh to Christopher Robin

There are many other examples of toys who get lives of their own, but these to me will always stand out. Many of them are profound reflections on human experience, and it says something about all of us that the easiest way to learn about ourselves is to return to those elements that shaped our childhoods. Perhaps that is why stories about toys who are people (and the ones who love them so dearly) are still important.

This article was originally published in December 2013.